“A lot has been written and spoken about the Dyson family […], the majority of which was unmitigated bunkum…”

Edwin Greenslade Murphy aka “Dryblower” wrote this in 1927 on the death of a very prominent (pun intended) member of said family. The well-known Sunday Times scribe and popular poet was in an excellent position to know as he had written much of it.

Dryblower‘s inventions were (mostly) affectionate as he counted the recently deceased Andrew “Drewy” Dyson a friend. From his insider’s position he made tantalising mention of

“…those who have been privileged to see the pictures and paintings of Drewy’s ancestors, the family Bibles, the old oaken cabinets, caskets, etc, were given a peep into a past that was full of interest and history.”

Andrew “Drewy” Dyson (1858-1927) was one of twenty-one children that the Western Australian colonist James Dyson was believed to be the father of. There were at least forty-four grandchildren, seventy-eight great-grandchildren, and beyond that generation the white-noise makes an accurate count of numbers near impossible. The peep into the past that Dryblower could gaze on — that has long been dispersed, and may no longer even exist.

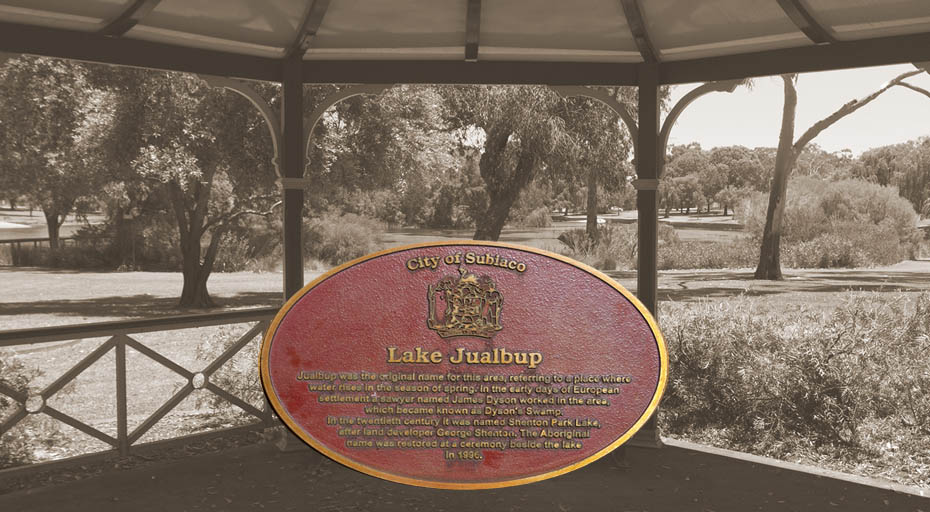

James Dyson was a man who had a swamp named after him. He and his family were cultural institutions during the second half of the nineteenth century, and the beginning of the twentieth, in Perth, Western Australia. If his son Drewy had been about in the twenty-first century he would have been an internet meme and social-media superstar.

So who was James Dyson?

James Dyson was about 31 when he arrived in the Colony of Western Australia on 11 July 1841 on the Colonial whaling barque Napoleon. The certificate of his marriage to Frances (Fanny) Hoffingham in October of 1942 is the earliest mention of Dyson in print in the Swan River Colony. He gave his age as 23, but he was certainly lying.

His occupation is listed as labourer. On the birth certificates of his first four children he was more specifically described as a pit-sawyer. In 1845 he won a tender to supply timber for the construction of the Aboriginal Institution (a prison) on Rottnest Island. This is not the same structure — known as the Quod, that exists today— This second gaol was constructed after the original was burnt down by the superintendent, while attempting to smoke out some escaped prisoners. (But where were they going to escape to on a small island?) Irrespective of this, Dyson was also paid by the government for some materials used for the surviving replacement. His career as a successful timber contractor, merchant, butcher, baker, man of property and Perth City Councillor was established.

The first shipload of convicts landed in Western Australia on 1 June 1850, transforming the free colony into a penal settlement. Dyson’s infant daughter had died, and he was left with three boys to care for between the age of 7 and 3. Enter Mrs Edwards who was looking for a place to stay.

The former Miss Jane Develing only arrived in the Colony in October of the previous year— she swiftly married Mr Richard Edwards— and gave birth to her first child (but not in that order), all before the age of eighteen. When her husband fell on hard times, Jane might have been employed by Dyson as nurse to his young family.

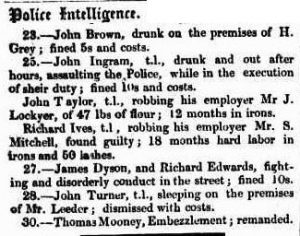

In 1853, she gave birth to her second child, whose name was registered as James Edwards. Some time later both her husband and James Dyson were arrested for brawling down the main street of Perth. Richard Edwards vanished from the public record and presumably the colony some time after that.

Afterwards, James’ own wife Fanny was lost, but Jane and James lived together for a further eight years before they were finally able to be married. The two children allegedly by her first husband took the name of Dyson, and a further four children were born before their parent’s church wedding in 1861 have no birth certificates at all.

Dyson’s business flourished under the early years of the convict system, even if his social standing was dubious. He became one of the largest employers of labour in the colony— Convict labour was employed for cutting timber, brick making, herding and slaughtering cattle. He began to build up a small real-estate empire. He owned a store and house on the corner of Murray and King Street in Perth. He was not an extensive land owner by the standards of the colony’s elite but he was a significant one. Lake Jualubup in present day Shenton Park was more commonly known in this era as Dyson’s Swamp. It was near this water, in late 1859, that his eldest child George died in a horrific accident involving a bullock cart.

Money talked. By 1860, Dyson had reached a threshold of wealth where some measure of respectability could not be denied him. He was eligible to serve on juries, but more importantly, as a rate-payer, he had the right to vote in elections for the Town Council of the City of Perth, and for the Road Boards on the Canning and around Perth. He may have been under the patronage of George Shenton senior (1811-1867). Possibly the most successful and influential merchant in the colony—and most devout and pious Christian—was tickled by the evidence of an indubitable sinner reformed. James Dyson and Jane had their wedding in the Wesleyan Chapel on William Street to Jane on 25 February 1861, and their remaining eleven (yes 11) children were all born within wedlock. Shenton gifted James a family bible in 1864. He also sold him the land that became known as Dyson’s Swamp. Years later Dyson was compelled to sell the land back to Shenton’s son.

Enter “Drewy”

In 1867 another of Dyson’s children, a boy of nine, was lost in the dense bush around Armadale. He had wandered away from his father’s convict timber cutting party with only his dog for company and was lost in the trees. This was the first mention (but far from last) of Andrew (later Drewy) Dyson in the colony’s newspapers. His distraught father rode out for the search only to be re-united with the child at Narrogin (as Armadale was then called, most confusingly). Later that year James was elected to the Perth City Council as a councillor for the West Ward, a seat he would hold for nearly a decade. The most notable event during Dyson’s tenure on the council was the construction and opening of the Perth Town Hall. It may be just coincidence (and those are pigs wheeling in the sky overhead) that this period coincides with Dyson winning many contracts to sell timber to city, used mostly for kerbing on the pavements.

The later years of Dyson’s life were marked by what were euphemistically described as “reversals” and the unravelling of his family life. His lands had to be sold. A young son shot a business rival’s even younger son in the head during a hunting expedition (both survived, but Dyson’s child was exiled to Victoria). Dyson was compelled to move into the home of his eldest son Joseph on the corner of Murray and William street (This corner also was known as “Dyson’s Corner,” not to be confused with the first “Dyson’s Corner” on King and Murray Street). His marriage failed.

Jane left James, or was thrown out of the house by him about 1883—Accounts vary. She was then convicted of theft from her new employer, who was an old associate of her husband. After she had served her time (during which another one of their children— Samuel—died aged 17), she took many of the younger children with her and founded what became one of the most successful brothels in Perth during the gold rush boom of the 1890’s— but that is another article. While Jane was still in the old Perth Gaol, her son, Andrew “Drewy” Dyson, now with the reputation as one of the meanest drunks in the colony, and freshly released from hospital after a suicide attempt, lurched back to the family home and beat up his elderly father. He was sent back to gaol for another six months, but Drewy’s redemption and fall and redemption and fall and unexpected lottery win was to far eclipse the fortunes of his father.

James Dyson, who was not born in Manchester, Lancashire, England, about the year 1810, would have been very familiar with the concept of a friendly societies, particularly the International Order Of Oddfellows (IOOF). Their purpose was to provide a form of life and health insurance to workers in an era before any form of social security. This they did, combined with the old-boy’s-club fraternity of quasi-secret societies such as the freemasons.

The Sons of Australia Benefit Society had been formed in Western Australia some years before Dyson had arrived in the Colony, and bore much the same relationship to the Oddfellows as the “Hungry Jacks” franchise in Australia does to “Burger King”. The Sons of Australia Benefit Society had been favoured with the grant of some prime real estate from the the government during their early days, which ensured that even when their membership was low, their balance sheet was always healthy. When Dyson first joined is not yet ascertained, however he was openly associated with the organisation by the early 1860’s when he rose steadily to be treasurer then, vice-chairman. His son Joseph was also a member and eventually became chairman and a trustee.

When Dyson died at Joseph’s house on 18 June 1888, allegedly at the age of 77, the annual celebratory dinner for the Sons of Australia Benefit Society was immediately cancelled as a mark of respect. He was buried in the family plot in what is now known as the Old East Perth Cemetery with his first wife, assorted predeceased children, and then much later his second wife Jane, after she died in 1899. The rare surviving headstone in the cemetery was erected by James and Jane’s son, Drewy — now a Funeral Director and a notorious identity in the last days of pre-federation Western Australia.

This was the end of James Dyson’s life, but it is far from a complete telling. A tale of murder and mayhem hid behind a respectable countenance.

His sixteen surviving children themselves all spawned legacies, heroic or squalid, mundane or perverse, outrageous or conventional, sometimes surpassing that of their father. It turns out that one of those threads leads right to me. Maybe I shouldn’t be so proud of that, but I am.