I started writing this story for posting about the time of Valentine’s Day but only now that it’s St Patrick’s Day do I find myself completing it. This is not altogether inappropriate as ultimately this is a love story from Ireland. It was difficult to complete for all the usual reasons all family history can be difficult to write: There is always the hope that some new fact will come to light, but when it does every thing you thought you knew has to change. But also:— this is a love story with a happy ending, and religion plays a positive role in the couple’s happy ending even as it compounded the inexpressible misery and horror of events swirling around them. All these facts are as confronting to my worldview as it would be to discover proof positive unicorns are real.

First: some backstory. In the year 1845, the island of Ireland stood on the brink of disaster. Two out of every five people depended solely on the potato crop for their survival. That year the potato crop failed. Seven is a nice apocalyptical number and that is roughly the number of years the great famine endured. At the end of that time one in every four man, woman or child who was in Ireland in 1845 was no longer. Over one million were in their graves, the rest were over the seas, some in the colonies of Australia; such was the fate of two young orphans: George Astley and Mary Chapman.

Being orphans, they were without family protection. Mary’s parents had died when she was an infant. She was never taught their names. George was in the care of an uncle for a while, but he too may have been gone before his time. His uncle’s family name was either Astley or Fulton. Whether he was the brother of George’s father, named George or his mother, Mary, is not known. George Astley, junior, also had a sister, and by her record we also have a good idea that George’s uncle was dead or no longer in a position to look after his nephew and niece by the middle years of the famine.

Mary Anne Astley died in the poor house of Carlow town, County Carlow and was buried in an unmarked grave at the institution’s burial ground on 14 March 1848. She was only twenty years old. George Astley and Mary Chapman were both about the same age, perhaps a year older. Whether they were also in the poor house, also known as the workhouse, is not yet uncovered. To be in such a place was the last resort for those with no other hope. Yet George and Mary did have hope, and the vehicle for that hope was part of the same mechanism that had bogged Ireland and the two young orphans in the slough of despair that currently engulfed it: British misrule and the Protestant church.

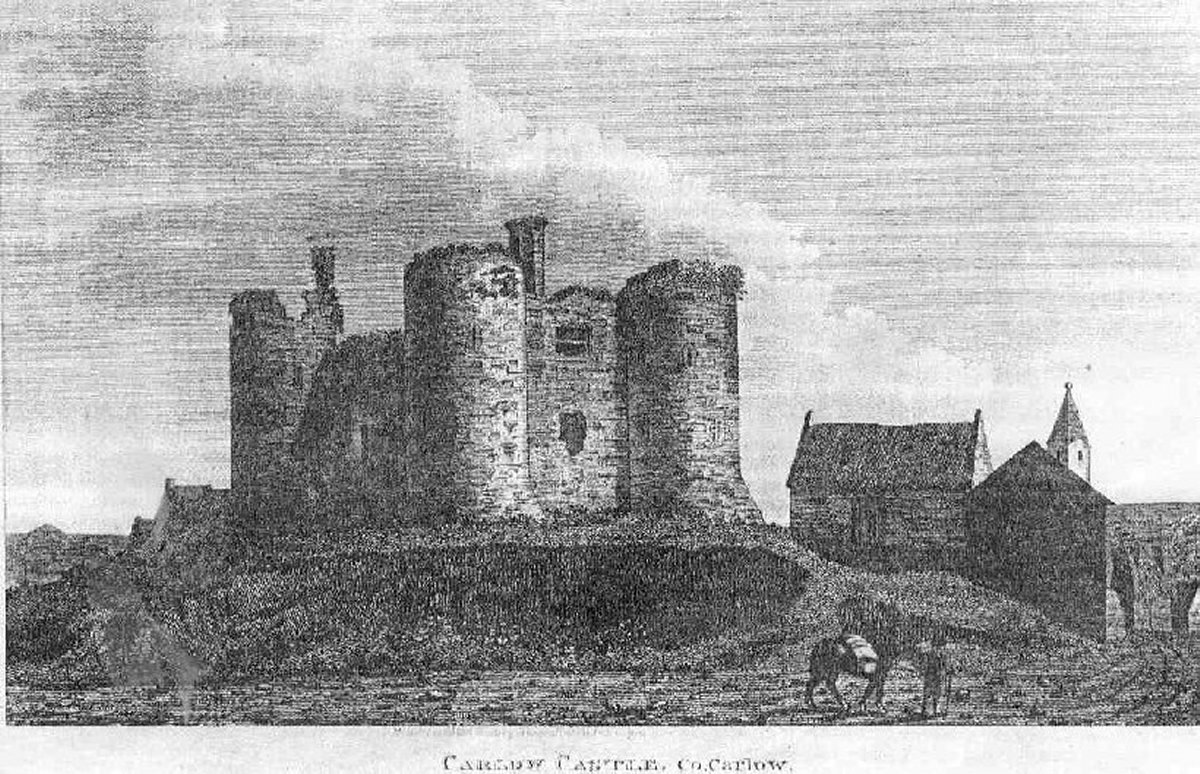

Young Mary and George would have known well the ruins of an ancient castle that dominated the centre of Carlow town. It had been mostly demolished some years before they were born (Irrelevant aside: blown up in an abortive attempt to turn it into a lunatic asylum) yet it remained a symbol of foreign domination of Irish culture and politics by a foreign power as it had been for centuries. Construction of the castle was attributed to the famous Anglo-Norman head-kicker William the Marshal in the twelfth century CE, but let us forward four hundred-odd years to the reign of the English Monarch Henry VIII. He is an easy scapegoat as any to blame for the mess Ireland was in at the time of the famine, or for that matter, our time in 2018.

Henry the pig-face is the perfect illustration of how you can have all the historical tides of sociological, cultural and political inevitability you like indicating change in a certain direction, but it the end it can all boil down to one human and one decision to change the course of history. In this instance it was Henry’s decision to make himself the head of the Christian Church in England in place of the Bishop of Rome.

In any other century this might not have been such a big deal, after all, it was not so long ago there had been more than one Pope (some times as many as three). As far as Roman Catholic unity went, it was also not long since that the troops of the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V sacked Rome and imprisoned the then current Pope Clement VII. But Henry’s new Church of England (and its Irish equivalent, the Church of Ireland) could never quite extirpate the old loyalties to Rome, the fault line amid the population widened as the doctrinal differences evolved between the adherents to Roman Catholic Church and those who identified themselves as Protestant. All this because Henry wanted to shag a girl he wasn’t married to…

Three hundred year after the break from Rome, there was not much point in trying to make the case who had the better moral argument to survive. Both sides had gained the upper hand politically at various occasions, at which point they would persecute without mercy whoever happened to be the underdog. By the beginning of the nineteenth century, this was the situation in Ireland: The population was roughly three quarters Roman Catholic with the remainder being adherents of the Church of Ireland or Scots Presbyterian. However, members of the Church of Ireland had the monopoly on political and economic power. When Ireland was formally absorbed by Great Britain into the United Kingdom and its native parliament abolished in the year 1800, this signalled, paradoxically, the beginning of the end of this era of unrestrained power (and the abuse thereof) exercised by the Church of Ireland on behalf of its followers, during what was self-explicably described as the Protestant Ascendancy. Over this period Catholics (and Presbyterians too) were denied the franchise and just about every other conceivable human right. But the pendulum of power was swinging slowly in the other direction: during the nineteenth century the Church of Ireland was slowly stripped of its secular power: Tithes were scaled back and finally abolished, eventually the Church was abandoned by the state and disestablished towards the later half of that century. By 1845 Protestants in Ireland, although they then still had total control over the law of the land, ownership of the same, and all the civil apparatus of government, must have seen that their days of unfettered control slipping as Catholics slowly regained their right to vote, own property, educate their people, and be employed by the very government itself.

So who were these Protestants? They were concentrated mostly in the north of Ireland, which contained the few counties where they were (and still are) a majority. They were immigrants from Scotland and England, but many families had lived in Ireland for generations, some dating back to the Norman invasion. Some Anglo-Irish families could be indistinguishable from the native Irish in language and custom. It’s foolish to talk about pure Irish, or pure anyone. I know nearly half of my own ancestors originated from the far north of Scotland and had been there for uncounted centuries: They are Scots. Yet according to science nearly half of my DNA indicates an original homeland in Ireland. There were certainly many Protestants who were native Irish, but the fact remained that the Catholic religion remained a majority in the country if for no other reason than as a reaction to British rule.

The Protestants did themselves no historical favours. When in 1798 Ireland erupted into full rebellion against the British Crown and the Irish parliament in Dublin, the revolt was violently suppressed. Because the majority of the rebels were Catholic even as the United Irishmen themselves had Protestant leaders, zealots could choose to present it as a sectarian conflict and did. One of the set-piece battles took place in the town of Carlow on 25 May 1798, where prior to the bloodbath, relations between the Catholic and Protestant inhabitants of Carlow had been characterised as “friendly”. Without a single casualty on their side, the British Army killed about 500 civilians and rebels (No distinction was made). Another 150 were summarily executed in the aftermath. Wading though the blood were such characters as the Reverend Robert Rochford, known as the ‘slashing parson’.

“In a very short space of time, Orangeism, Protestantism and oppression became synonymous concepts in the minds of the Catholic population.”

Shay Kinsella, The ‘slashing parson’ of ’98, History Ireland, Jan/Feb 2014

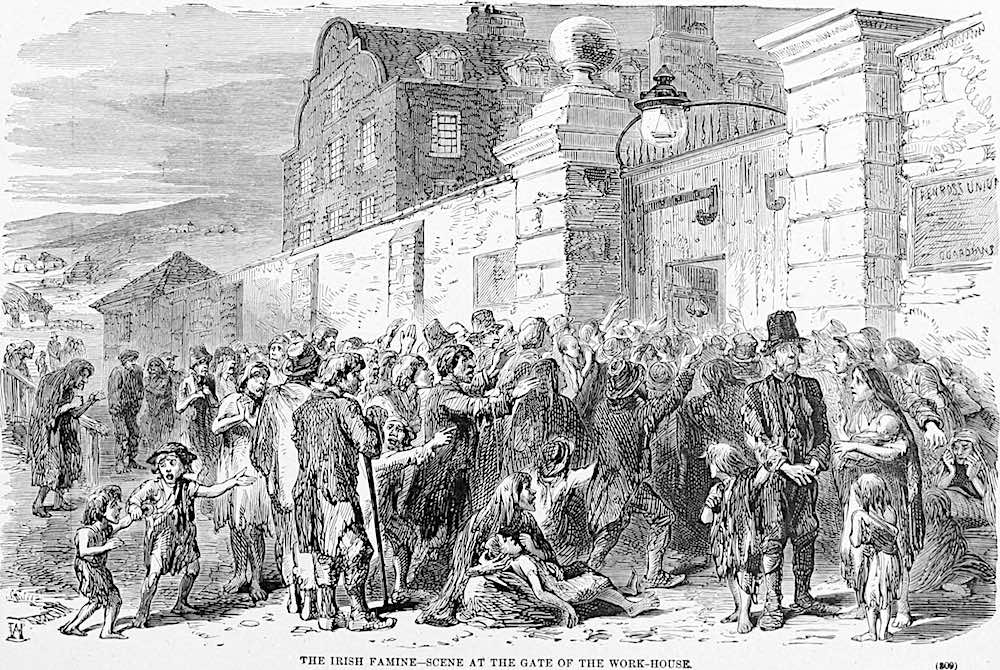

In 1845, when the great famine began, the end (however remote) may have been in sight for Protestant domination of (most of) Ireland, but direct rule from London had brought with it new institutions such as the Poor Laws, and the Workhouse—run exclusively by Protestants. Most Catholics would rather have starved than enter the Workhouse, and that was the point. Being poor, without a home, or starving was practically a criminal offence and workhouses were the gaols. During the peak of the famine the workhouses became concentration camps for those evicted from their homes for being unable to pay their rents due to the failure of the harvest; for those who could not afford to pay for what food there was, as the Laissez-faire policies of the Government saw food shipped out of the country because that was where the profit was. But Laissez-faire ideology stretched only so far: for fear it might hurt the bottom line of the local magnates and land owners, imports of food to Ireland were barred by the government. Mediocre food and poor accommodation in the workhouse bred the inevitable result: disease.

In Carlow, the poorhouse building has been long demolished, but on the site of the burial ground where Mary Anne Astley lies, there is a monument to the over three thousand men, women and children buried there who were “victims of poverty, famine, cholera and injustice” (according to the inscription). If you were Roman Catholic in Ireland, you were given no good reason to love your Protestant neighbour; he was probably your landlord or on the board of governors for that local poorhouse. But here was a twist: the late Mary Anne, her brother and his sweetheart too; all three were Protestants, all members of the Church of Ireland. Both Chapman and Astley are names of English origin, but how long their families had been in Ireland cannot be known. In 1848, none of them had a family. Ultimately, a Protestant could starve to death in the workhouse just as well as a Catholic, so how did George Astley and Mary Chapman survive?

In Australia.

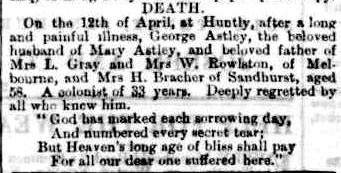

Huntly is a small town in rural Victoria several kilometres north of the mining metropolis of Bendigo. Huntly was also a mining region in its own right back during the gold rushes of the late nineteenth century. It was here that George Astley and Mary Chapman made their final life together. George was a local government contractor, which meant that he must have been able to turn his hand to just about anything. They were married for thirty years until George’s death in 1885 at the age of only 58. Mary outlived him by nine years and they were finally re-united at the White Hills Cemetery outside Bendigo. This is quite a puzzle as George had been involved with a Cemetery Board for Huntly. Why were the couple not laid to rest there? The site of their grave at White Hills has been lost, but that is a rant for another article.

The couple were both deeply invested in the civic life of the Huntly community; the meeting about the above-mentioned local cemetery was but one example. George was on the local School committee, and involved in local government politics, but it was as parishioners and members of the board of the local Church of England parish that they and their family were most committed (It is worth observing that the local school was an Anglican-run institution at the time of his membership on its board). Their strong connection with this church is documented in the numerous mentions of family names in the contemporary newspapers in connection with High Church business, often concerning quite absurd personal disputes that thankfully, they seemed to remain on the periphery of.

One of their sons, George Alexander, and a daughter, Rebecca Edith, were both recorded being awarded prizes at the anniversary celebrations for the Church of England Sunday School during 1879. It is thanks to this son, one of seven out of ten children George and Mary had together who lived to adulthood, that we have some clue as to how his parents survived Ireland, and indeed met in the first place.

According to a letter written by George, preserved in the archives of the Huntly Districts Historical Society (without whose kind and generous cooperation this article could never have been composed), his parents met at school back in Ireland and there became lovers. That is their son’s own word for their relationship.

Which school?

A gazetteer for Carlow in the year 1839 describes the following:—

“A Parochial School is aided by an annual donation from the Rector of £10. There are two National Schools and an Infant School — a Ladies’ Association, for bettering the condition of the Female Peasantry — a Protestant Orphan Society, where the children are clothed, dieted, lodged, and educated — a Cloathing [sic] Fund Society, and a Fever Hospital. The District Lunatic Asylum for the counties of Carlow, Kildare, Wexford, Kilkenny, and the County of the City of Kilkenny, is situated in this Town, and was built in 1831 at an expence of £22,552, 10s. 4d.;- it is under excellent regulations, and is calculated to accommodate 104 Lunatics.”

Shearman’s Directory New Commercial Directory for the Town Carlow

One day it may be possible to investigate the records of these institutions located in Ireland, but for the moment only the calculation of probabilities says that this is where they met, and where they obtained their rudimentary education—for it is a documented fact that while George Astley and Mary Chapman could both read, neither could write. Maybe that was sufficient to ensure their survival. They could read about the opportunities to get out Ireland, about schemes of sponsored immigration to such places as North America, or the distant colonies of Australia. That was a chance denied to most Irish Catholics. All the Carlow institutions mentioned in the gazetteer above had one thing in common; they were restricted in access to the Protestant minority, desperate to maintain their separate identity within an overwhelmingly Catholic majority—a majority who day by day they were giving more reasons to hate their guts.

George and Mary would get out of Ireland, but they were not yet married and the transit to the other side of the world would test their commitment to each other as much as anything they may have endured in Ireland, in the workhouse or beyond. When they set sail, they would never see Ireland again. But would their love survive the oceans?

Leave a Reply